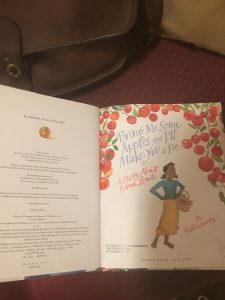

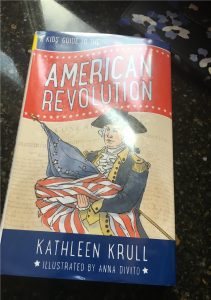

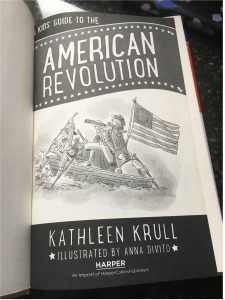

Author(s), Illustrator/Photographer: Kathleen Krull; illustrated by Anna Divito.

Publisher and Year/Number of pages: HarperCollins Children’s Books, 2018, 207 Pages.

Tags/Themes: Graham, New Nation, Declaration of Independence, Thirteen Colonies, Revolutionary War, Boston Tea Party, Washington, George, and Dano.

Genre: Nonfiction, Chapter Book.

Descriptive Annotation: The cover features a watercolor drawing of George Washington, kitted out in a traditional tricorn and blue frock coat, cradling a US flag (of the Thirteen Colonies) and superimposed over the Declaration of Independence. Also included is a red, white and blue color scheme in the title and author’s name as well, emphasizing the colors that the new nation of America rallied to in the heady days of 1776. This is a combination of both standard unifying American imagery used by our country since its independence, and the founding document of our initial independence being put in a position of prominence, which can be seen for the entirety of the novel.

A Kids’ Guide to the American Revolution is the beginning story of our country, which was a group of men who decided that enough British domination was enough, and despite their many differences, it made sense for them to band together and declare to the world the birth of a new nation, and, in doing so, made a document that changed the world: “It spelled out the reasons why the colonists had to rebel against the mother country and begin to govern themselves. It’s not exaggerating things to say that the Declaration launched America” (Krull, p. 7). As the book continues, it is evident that this American story as portrayed in this novel is the complex, conflicted one as it was in real life, mostly due to its older targeted audience. Also important is that this version of the American tale does have plenty of heart as well, and indeed makes the boosting of morale that George Washington did throughout the war for his troops in the face of difficult odds a key point of focus for the reader: “With these victories he wasn’t just scoring points. He was boosting troop morale and attracting much-needed recruits. Washington was doing more than any other single person to keep the flame of the American Revolution alive” (Krull, p. 139). The whole of the story is about the acceptance of revolutionary and Enlightenment ideals that posed a serious threat to the British governing order in the Declaration of Independence, and how the war was won based on those ideals even if they weren’t always practiced by all of the Founding Fathers at all times. All Americans of every age group, not just students, should read this book as well, because the author does an evenhanded job of assessing the reality of the Revolution for a book that was designed for children, and the lessons within would certainly be useful for students reading this novel in the primary school classroom.

Classroom Application: In the book A Kids’ Guide to the American Revolution, the characters are all real-life figures from the Revolution, from the top (George Washington, King George III) to the lesser-known heroes of the war, such as a man named Swamp Fox (who was in real life called Francis Marion), who had fought in the French and Indian War: “While battling-and almost losing to the Cherokee Indians, he admired how the Cherokee turned the swampy backwoods to their advantage, hiding until just the right moment for an ambush” (Krull, p. 157). This demonstrates how people take some of the best ideas from those with whom they may have clashed with before, and that competition can later turn into cooperation, as it did when “Marion’s Men” joined forces with their erstwhile indigenous foes to take down British forces in South Carolina during the Revolutionary War, using those same tactics. This is a teachable moment, since it’s Krull’s way of saying that America was built not on lasting enmity towards one’s foes, but treating them as friends once the current issue at hand has been resolved-just as Britain became a great ally in World Wars I and II, and how Germany and Japan are close allies with us to this day as well after we defeated them in the Second World War as well. In short, we need to embrace the lessons learned of the Revolution and strive towards a world with less enmity and lingering resentment in any way possible. This book is an excellent primer on how to do just that by looking at examples from our primary history way back in the 1770s.

Linguistic and Cultural Diversity Analysis: Krull covers the interactions between American and Brits, colonizers and the colonized, slave and freedman, and does so in a way that doesn’t gloss over the real pain that has occurred in our past through many faults of our own. The end of the war didn’t solve the issue of slavery in the slightest-it exacerbated the problem in many ways, as Krull acknowledges: “The institution of slavery continued to be practiced in the original thirteen colonies. Within days of the war’s end, plantation owners were paying soldiers to locate runaway slaves living in the surrounding woods” (Krull, p. 189). This is necessary to do, as many past versions of our founding have glossed over the often-sad realities that plagued our nation for generations and are still not truly solved. The author’s motivation was to do right by the lives of those who were historically ignored in our textbooks, and to do so in an engaging way that is not misguided or skewered to any certain degree: “Treaties made with the British prior to the war were ignored by the Americans, and years of bloody conflict and expansion destroyed some tribes” (Krull, p. 193). On those pages which cover the aftermath of the war, a nation was born divided between those who had and who had not, and recognizing that not all was peaches and cream is an important step in the telling of American historiography to young readers. In the context of the age group that is reading this book, it is understandable that it is included to help eliminate false truths.

.

.