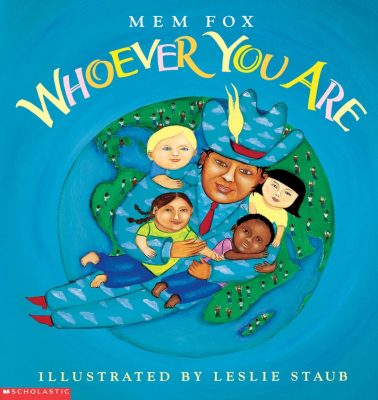

Title: Whoever you Are

Author: Mem Fox

Illustrator: Leslie Staub

Publisher: Voyager Books (1997)

Pages: 26

Genre: Realistic Fiction

The story is told from the perspective of a character I will refer to as the Journeyman. The Journeyman takes a group of 4 children around the world so that they can appreciate the differences, but also realize the similarity that unifies all people.

The story telling is very straight forward and to the point. The first half of the story explains all the differences that cultures have from one another. People may look different, be taught differently, talk differently, live different lives, and might have very different languages (the emphasis on very comes from the text). The special emphasis on the difference of language doesn’t quite make sense to me because individuals’ lives and cultures are also very different from one another. One could perhaps demonstrate how all these differences might be very different and how that ties in, or perhaps exclude the emphasis. However, the Journeyman does tell the children that the things that really matter are universal. From hearts to joy and from laughing to bleeding, we all have this in common.

All the images are framed and like specific paintings, or windows giving on the sense of being outside looking in. This works well with the book’s overall message, which is that we do have a degree of separation by our difference, yet we are still the same despite these separations. Most of the imagery is also straight forward, but there are some subtle things that could open up discussion in the story as well. Less importantly, the Journeyman and the children appear on at least every set of pages and so could play as a little game to find them, as they are small in some frames.

More important, however, there are two pages worth highlighting. The first is when the Journeyman and kids are observing how schools around the world may be different. All the children in this frame are boys and it is clear there are women in the back looking on in curiosity, anger and sadness. This perhaps lends itself to conversations about sexism in education abroad and locally. Secondly, when the Journeyman is explaining how hurt and its expression of crying is the same, a father is being separated from his child and there’s a bus in the background which could open up discussions of the reasons why such a thing would happen, ie. war, conflict zones, and refugees.

This book is relatively short, but gets the message across succinctly and nicely. While not the most conversational piece there are some subtle images that open up broader discussion. It highlights differences and explains how they are certainly a distinction between cultures and ethnicities, but that there are more universally known and strong feelings that unite us all as one.